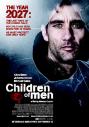

Children of Men, the movie

When did movies stop looking at the future with wonderment? 2001: A Space Odyssey was perhaps the last time the infinite possibilities of years to come were depicted as inspiring and expansive. In the last four decades, dystopia has reigned supreme on the big screen, and the time focus has got shorter and shorter. Now we look forward, myopically, only a few decades at a time, and what we see is so appalling it’s no wonder we desert the wider world and take refuse behind our iPods and computer screens.

Director Alfonso Cuaron’s just-released Children of Men (Cert 15), which is loosely based on PD James's novel, is the latest attempt to draw conclusions about the future from the mountainous problems of the present. And like so many other examples in this genre, the assumption underlying the whole story is that, in the interim, we have proved utterly powerless in the face of the chaos brought by complete social breakdown.

Cuaron’s film is of interest mostly because of the picture it paints of everyday life in Britain in 2027. The weak story comes a poor second. Women have been made infertile (possibly by a massive flu epidemic), no children have been born for 18 years, an authoritarian government is in charge and Britain is besieged by illegal immigrants who are kept in cages at ports and rail stations. Clive Owen plays a burnt-out, passive bureaucrat (reminiscent of Orwell’s Winston Smith) who is persuaded by a terrorist gang to help the escape of a young woman (Claire-Hope Ashitey) who somehow, miraculously, is pregnant. Hunted down by competing forces, Owen’s character finds himself acting heroically in the midst of gun battles despite a seeming lack of either conviction or compelling motive. It is, in effect, simply a chase movie.

But the background scenario is plausible in many ways, and in its details and atmosphere is thoroughly convincingly depicted. London still has its red double-deckers, but they are covered in moving video ads, albeit far grubbier and washed-out than those in Bladerunner. Random bomb explosions rock the streets. People look roughly the same, only their expressions are even more defeated and passive than can be seen now on your average commuter journey. Disposable euthanasia kits (‘Quietus - You decide When’) are sold over the counter. Groups of feral kids attack trains with rocks, and passengers barely turn a hair. Everywhere, people are encouraged by disembodied voices to report illegal immigrants.

However what makes all this imaginative production design finally hollow is the utter vagueness of the film’s political dimensions. We’re left in the dark about the political make-up of the predictably ‘fascist’ government; the terrorist group, maybe environmentalist, maybe anarchic, maybe simply ‘humanist’, seems to have little agenda. The immigration problem which features so largely is emotionlessly portrayed - we’re not quite sure whether we’re meant to view the obviously inhuman treatment of these arbitrarily imprisoned (and apparently mostly Eastern European) refugees as the cause of the turmoil, or the result of it. All this makes it hard to become more than merely superficially involved.

And yet at the same time, it is this very vaguenes which makes the film interesting when viewed from our beleaguered present. We’ve become used to seeing a largely left-leaning vision of the future where the corporations are the root of all evil (as in Rollerball), or where a specifically right-wing Tory government crushes all dissent (the absurd V for Vendetta), or more weirdly still, where past liberal battles are played out paranoically as though they’re still being fought (the ghastly and pointless remake of The Stepford Wives, or The Handmaid’s Tale). But the ambiguity of Children of Men reflects not just the loosening of labels, and perhaps the death of genuine political debate, which characterises our own times, but the free-floating anxiety which consumes those who would still identify themselves as being of the Left and Right. Both points of view could find support for their arguments in the film’s portrayal of a multi-cultural London in the midst seemingly of a slow-motion civil war, and certainly the central conceit of an infertile population could be seen as a metaphor for Europe’s catastrophically plunging birth-rate. What, finally. touches a highly-exposed nerve is not just the sense that, despite the ceaseless efforts of the capital’s boosters, London is recognisably already on the way to this nightmare vision, but that social and moral fragmentation has led to an overwhelmingly nothingness at the very centre of things.

Director Alfonso Cuaron’s just-released Children of Men (Cert 15), which is loosely based on PD James's novel, is the latest attempt to draw conclusions about the future from the mountainous problems of the present. And like so many other examples in this genre, the assumption underlying the whole story is that, in the interim, we have proved utterly powerless in the face of the chaos brought by complete social breakdown.

Cuaron’s film is of interest mostly because of the picture it paints of everyday life in Britain in 2027. The weak story comes a poor second. Women have been made infertile (possibly by a massive flu epidemic), no children have been born for 18 years, an authoritarian government is in charge and Britain is besieged by illegal immigrants who are kept in cages at ports and rail stations. Clive Owen plays a burnt-out, passive bureaucrat (reminiscent of Orwell’s Winston Smith) who is persuaded by a terrorist gang to help the escape of a young woman (Claire-Hope Ashitey) who somehow, miraculously, is pregnant. Hunted down by competing forces, Owen’s character finds himself acting heroically in the midst of gun battles despite a seeming lack of either conviction or compelling motive. It is, in effect, simply a chase movie.

But the background scenario is plausible in many ways, and in its details and atmosphere is thoroughly convincingly depicted. London still has its red double-deckers, but they are covered in moving video ads, albeit far grubbier and washed-out than those in Bladerunner. Random bomb explosions rock the streets. People look roughly the same, only their expressions are even more defeated and passive than can be seen now on your average commuter journey. Disposable euthanasia kits (‘Quietus - You decide When’) are sold over the counter. Groups of feral kids attack trains with rocks, and passengers barely turn a hair. Everywhere, people are encouraged by disembodied voices to report illegal immigrants.

However what makes all this imaginative production design finally hollow is the utter vagueness of the film’s political dimensions. We’re left in the dark about the political make-up of the predictably ‘fascist’ government; the terrorist group, maybe environmentalist, maybe anarchic, maybe simply ‘humanist’, seems to have little agenda. The immigration problem which features so largely is emotionlessly portrayed - we’re not quite sure whether we’re meant to view the obviously inhuman treatment of these arbitrarily imprisoned (and apparently mostly Eastern European) refugees as the cause of the turmoil, or the result of it. All this makes it hard to become more than merely superficially involved.

And yet at the same time, it is this very vaguenes which makes the film interesting when viewed from our beleaguered present. We’ve become used to seeing a largely left-leaning vision of the future where the corporations are the root of all evil (as in Rollerball), or where a specifically right-wing Tory government crushes all dissent (the absurd V for Vendetta), or more weirdly still, where past liberal battles are played out paranoically as though they’re still being fought (the ghastly and pointless remake of The Stepford Wives, or The Handmaid’s Tale). But the ambiguity of Children of Men reflects not just the loosening of labels, and perhaps the death of genuine political debate, which characterises our own times, but the free-floating anxiety which consumes those who would still identify themselves as being of the Left and Right. Both points of view could find support for their arguments in the film’s portrayal of a multi-cultural London in the midst seemingly of a slow-motion civil war, and certainly the central conceit of an infertile population could be seen as a metaphor for Europe’s catastrophically plunging birth-rate. What, finally. touches a highly-exposed nerve is not just the sense that, despite the ceaseless efforts of the capital’s boosters, London is recognisably already on the way to this nightmare vision, but that social and moral fragmentation has led to an overwhelmingly nothingness at the very centre of things.

Peter Whittle

2 comments:

Release dates for Children of Men:

UK 22 September 2006

Japan 7 October 2006

France 18 October 2006

Russia 19 October 2006

Netherlands 26 October 2006

Germany 9 November 2006

USA 25 December 2006 (limited)

USA 29 December 2006

More countries on Imdb

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0206634/releaseinfo

Good readiing

Post a Comment